On the Pitfalls of Parenting

Being a parent is really hard.

I'm tempted to stop this post there-- everyone will agree with me and really, enough said.But alas, I have a story to tell.The other day someone I sort-of know (we are in the same writing community, but don't know one another terribly well) posted an article about picturebooks about anxiety that she thought silly. In her introductory comment, she wrote:"Let's face it. Kids have more anxiety because there are fewer children being parented. I mean, do you honestly think a picture book is going to give a child the courage to say: "I feel anxious when you want me to attach to whoever you bring into the house. Quite frankly, mom, I've had three nannies and attended four different schools in your misguided attempt to give me the "best." That's a lot for a seven year old to deal with." Or maybe: "I understand that pot is legal and that I won't get high if you smoke it in the other room while I sleep, but the THC in the air still gets into my system. Because of my lack of a blood/brain barrier, it deposits into my brain creating paranoia for hours and days later." Of course not. And these are just two of the myriad of issues children are dealing with today."**Um. First: WTF does that even mean? Those examples are like, off the wall.And then the rage set in.Now I know better than to engage in a debate over Facebook, really I do. But I couldn't get past this one -- particularly because it was written by someone who is not herself a parent.So I replied with this:"Your assumptions on mental illness are both off and, frankly, offensive. Your oversimplified take reminds me of when autism was blamed on "refrigerator mothers" -- in other words, before we knew better. Mental illness is real. It is hard wired. By your logic, I am to blame for OCD, anxiety, depression, ADHD, and autism (which isn't a mental illness, but is also hardwired, and it usually comes with anxiety and other mental illnesses). It's especially offensive in that your parenting experience is by proxy. I literally spend my entire life advocating for my kids because of their mental health issues. And they spend their time struggling and working their asses off to combat those demons. Anxiety is not something you can "give" your children."To which she replied that I was missing the point. At which time I just decided she and her ridiculous viewpoint simply wasn't worth my time.Why am I telling you this? So you'll be outraged with me, of course.But mostly to draw attention to the fact that PARENTING IS REALLY FREAKING DIFFICULT.Whether or not your child suffers from a mental illness.And it's made all the more so by the judgement of others, who both implicitly and explicitly suggest that your children's traits are a direct result of your poor judgement as a parent.And it's hardly just about mental health. It's "that dress is too short" and "I would never let my kid leave the house like that." And "someone should teach that kid a lesson" and "if my kid acted like that I'd...." Apple, tree, etc. You get it.If you haven't read Andrew Solomon's astounding book on this very topic, aptly called Far From the Tree, you should. Immediately. It's pretty hefty at over 900 pages, but now there's a YA version out too that makes it more accessible for those who prefer not to lift weights and read at the same time (or anyone looking for a less technical read). This book is a study of being human, and should be required reading for absolutely everyone. From my review of the Young Adult edition: "[t]he powerful young adult adaptation of the 2013 book examines the intricacies of family dynamics: how do the Columbine killers’ parents, for example, cope with their children’s legacy? How does the behavior of a severely autistic child affect his family? Told with astounding empathy for both parent and child, Solomon probes the myriad ways “vertical identities” (those we share with parents) intersect with “horizontal identities” (traits not shared) to create subcultures of identity where our differences are what makes us human."Each chapter title dictates a different horizontal identity that a parent must both love her child and contend with simultaneously; the titles are "Deaf," "Dwarfs," "Down Syndrome," "Prodigies," "Schizophrenia," "Rape," "Disability," and so on. Nowhere does Solomon blame a parent or a child for the "intersection of identities" that are complicated and beautiful and messy and loving and eye-opening and community-building. Often at the same time.I think about Solomon's book a lot now as I review, read, and write. I write for children, but I want to empathize with their parents too, in order to tell a story that feels true. In another post I wrote about an overweight girl's mother being just about the worst mother in the world for the way she fat-shamed her daughter. Maybe I was being unfair or, at the very least, reductive. Sure, this mother was pretty awful. But maybe that means the character needed to be developed more fully; no one is just one thing, after all.

From my review of the Young Adult edition: "[t]he powerful young adult adaptation of the 2013 book examines the intricacies of family dynamics: how do the Columbine killers’ parents, for example, cope with their children’s legacy? How does the behavior of a severely autistic child affect his family? Told with astounding empathy for both parent and child, Solomon probes the myriad ways “vertical identities” (those we share with parents) intersect with “horizontal identities” (traits not shared) to create subcultures of identity where our differences are what makes us human."Each chapter title dictates a different horizontal identity that a parent must both love her child and contend with simultaneously; the titles are "Deaf," "Dwarfs," "Down Syndrome," "Prodigies," "Schizophrenia," "Rape," "Disability," and so on. Nowhere does Solomon blame a parent or a child for the "intersection of identities" that are complicated and beautiful and messy and loving and eye-opening and community-building. Often at the same time.I think about Solomon's book a lot now as I review, read, and write. I write for children, but I want to empathize with their parents too, in order to tell a story that feels true. In another post I wrote about an overweight girl's mother being just about the worst mother in the world for the way she fat-shamed her daughter. Maybe I was being unfair or, at the very least, reductive. Sure, this mother was pretty awful. But maybe that means the character needed to be developed more fully; no one is just one thing, after all.

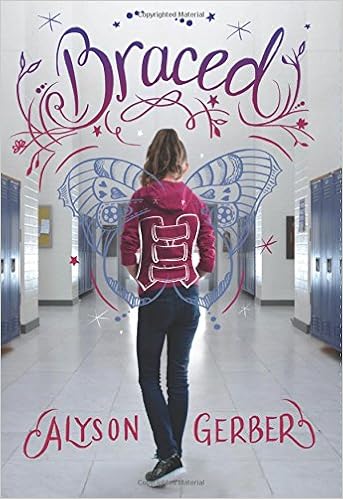

I reviewed another book that gives me pause when I think about its depiction of parenting. In Braced by Alyson Gerber, seventh grader Rachel has severe scoliosis and her life is turned upside down when she is forced to wear a hard plastic brace that extends from her shoulders to her hips. Shopping for clothes becomes impossible and frustrating, she can no longer kick a soccer ball, risking her hard-earned spot on the team, and she’s earned the unfortunate name “Robo-Beast.” Worst part: even her mother doesn’t understand.

that extends from her shoulders to her hips. Shopping for clothes becomes impossible and frustrating, she can no longer kick a soccer ball, risking her hard-earned spot on the team, and she’s earned the unfortunate name “Robo-Beast.” Worst part: even her mother doesn’t understand.

While Rachel’s struggles to determine how to fit in when you look different is poignant, it turns out that as a child, her mother also had scoliosis. So to her, a brace like the one Rachel wears would have spared her major surgery and a lifetime of physical back pain. For mom that outweighs the social foibles of middle school. But not to Rachel, who lacks the perspective of hindsight. Rachel thinks her mother just doesn't get it; her mother can't understand why her daughter isn't more grateful for her situation. It's a wonderfully honest premise for a story.In many ways, our kids pop out as who they are. When a neurologist recently asked me when we first saw signs of Teenager's autism, I said something like, "well in hindsight: birth."He needed to be swaddled tightly and didn't outgrow it quickly like my friends said their babies did. He didn't focus in the same way as the other babies in playgroup. He cried more. He didn't sleep train like other kids, and as a toddler was shockingly averse to subtle tastes and textures that other kids popped in their mouths thoughtlessly. But he made eye contact. And smiled. And showed love -- the signs of autism doctors most often watch for.He was who he was. And he was my first, so what did I know?He's still who is who he is. And I try my best to parent that child, and not some figment of my imagination likely created from an amalgam of teaching kids, reading books about kids, and my own childhood. Because truthfully, my kids are even better than anything I could have imagined: both are real and complicated and never in a million years could I-- as a parent OR as a writer-- have dreamed either of them up. Sure, there are some parts of me and my spouse in them, but they are unique, too.If I'm an apple tree, Teenager is say, a pear, or maybe a peach. Tween is, oh, I don't know... is there a witty fruit you can think of? He's something zesty, hard to describe but freaking delicious if baked into a pie.I don't think my choices as a parent have a lot to do with them being who they are.They are themselves. I just love them the best I know how.

Mental illness is real and needs to be discussed openly, with honesty and empathy.

Without shame.

This is why I write books for children. This is why I read.

The world is so much bigger than what I see from my small window. Open it wider. Step outside. **Just in case someone was skimming, let me reiterate: I DID NOT WRITE THIS SECTION. AND IT REALLY PISSES ME OFF.